Kharkiv Metro | Photo by Taras Zaluzhnyi on Unsplash

By Joe Lindsley, Kateryna Bortniak and Vitalii Holich

Three reporters in Lviv, in Ukraine’s west, one of them a Kharkiv native, travelled to the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, just 20 miles from Russia, to understand the mood and realities in the shadow of the Moscow threat.

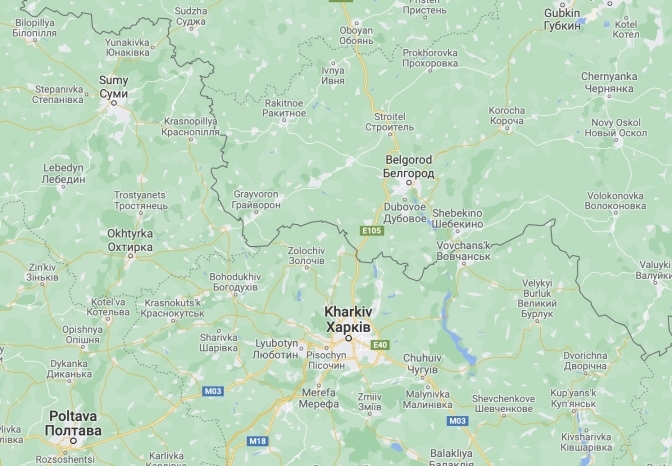

Kharkiv, Ukraine – Arriving at the Kharkiv railway station after the overnight sleeper train from Kyiv, we heard a taxi driver asking if anyone needed a ride to Belgorod, a Russian city, 70 km from Kharkiv. Even amid current strife, Russians and Ukrainians are still criss-crossing the border.

The sense of many outside observers is that there are many Russian sympathizers in Ukraine’s Eastern cities, including Kharkiv, because people of all ages chiefly speak Russian here. We have found a different reality: most Kharkivians are opposed to Russian rule. We have heard only a few accounts of people who pine for Moscow control, mainly the elderly, who stay at home and watch a lot of Russian TV or who once had good positions in the Soviet system. We hear about these people, but we have not met them.

But we have found people in an in-between category, what they call «neutral.»

Coming from fiercely pro-Ukrainian Lviv in Western Ukraine, where there is widespread distrust and disdain for Moscow, we were surprised to meet people who openly admitted to being «neutral.» And so we pushed to understand the mentality.

Open conversations even amid fears of war

And that’s the first thing to realize: Despite the recent threats from Moscow and the warnings of war from Washington and the global media, you can talk openly about these things in Kharkiv. There’s a feeling of free speech rather than clouds of fear or paranoia. And to our surprise, though we witnessed one alcohol-fueled argument among friends taking different sides on the matter of Ukraine and Russia, the neutral people and the pro-Ukrainians are seemed generally able to have civil conversations with each other.

Darya, a bookkeeper whose name we have changed for reasons that will be clear, is one of the «neutral people» with whom we spoke. We were joined in conversation by a Russian-speaking Ukrainian colleague of hers who, decidedly not neutral, is, completely pro-Ukrainian and anti-Moscow. Both of them agree: They don’t want to be ruled by Moscow.

But Darya says that she appreciates travelling to Russia and exploring its culture. Like many people in Kharkiv, she has relatives on the other side of the border and she likes to visit them.

«My sisters and brothers are from Kursk, Moscow, Veliky Novgorod. How can I love or not love those places? I just go there to visit my relatives,» she says.

Russia spies on Ukrainians who cross the border

But there’s a catch for those Ukrainians like Darya who wish to travel to Russia: At the Russian border, people tell us, the guards check you for Ukrainian loyalties. They look at your phone, examine your Facebook posts, your likes. If you have been loudly pro-Ukrainian, if you have put a Ukrainian flag on your profile page, you will likely not be allowed to enter or might even be arrested.

And so those with reasons to visit Russia, commercial and familial, must be careful and quieter: that is, «neutral.»

Such people «don’t say ‘I am from Russia’,» Darya says, «[but] they just have business there to survive.»

And she thinks that exploring Russian culture and cities is a good thing.

«I can travel to take a rest there. My children have to see what Moscow, Saint Petersburg are like.»

At the same time, despite the «neutrality,» the question of affiliation to Ukraine is definite.

«I don’t want Russia, why would I?» Darya says.

Kharkiv Is Less Russian-Influenced Than It Was in 2014

By all accounts, the cross-border traffic is nothing like it was before Ukraine’s 2014 Revolution of Dignity, when Russian license plates were commonly seen around this city, Ukraine’s second largest.

Kharkiv

«There were many common marriages [between Ukrainians and Russians],» says Ihor Balaka, a Kharkiv civic leader, real estate businessman, and an interviewer in the city’s press club. «Most of the cars you could see [before 2014] were on the Russian registration. People from Russian cities came here, because we had the big market «Barabashova,» and other establishments, which supplied Crimea, Donbas, and Russian people with goods.»

And in the uncertain days after the Euromaidan Revolution, locals report, Russians mysteriously entered the city by the busload, leading to a few days in April 2014 when a Russian takeover seemed possible.

But when Russian-backed fighters tried to take control of the city and establish the Kharkiv People’s Republic, Kharkivians (or Kharkovchane as they are called locally)

pushed back. With some help from an elite Ukrainian military unit, they kept their city Ukrainian. Many of the Russian sympathizers left the city, while pro-Ukrainian refugees, fleeing Moscow rule in the Ukrainian Donbas region, settled in Kharkiv.

Those events made many Russian-speaking Kharkivians decidedly anti-Russian rule.

«2014 made me anti-Moscow»: This is a common sentiment we have heard from many people. In our conversations here, some acknowledge the feeling against Moscow was, after eight years, beginning to wane, but now, amid the new threats, the sense of Ukrainian identity is strong.

One of the Kharkiv businessmen with whom we spoke, Viktor Bavykin, who is the head of a financial company that operates in real estate, told us he refuses to visit Russia.

He believes that the vast majority of Russians are chauvinists who don’t see the different mentality of Ukrainians behind the language similarity.

«They think that if I’m speaking Russian, then I have to think as they do. No, I’m already thinking differently. I rejoiced in the collapse of the Soviet Union and understood the philosophy classes in the university, where we were told that every empire would come to an end. Russia will also collapse, but that is her problem, not ours.»

A square in Kharkiv

For Viktor, the question of going to Russia, even as a mere tourist, is unacceptable.

He once had business connections in Moscow, but in 2014 he said no longer would he return there.

Talking about Kharkiv, Viktor doesn’t consider pro-Russian people as a significant part of the city’s population. Even in 2014, he says, the demonstrators who shouted slogans for the separation of East-South regions from Ukraine, were financed by outsiders, perhaps Moscow, and had nothing to do with the views of the majority.

«Half of the population was formless, without a position, while another part was strongly pro-Ukrainian,» he says. «There were some that disturbed the water, but no one attacked them with knives.»

In explaining her neutrality, Darya says she also fears the rhetoric that can lead to war. Her son, she says, wants to fight for Ukraine but she doesn’t want him to go to war.

«I gave birth to him, and some idiots start wars,» she says. She complains of the «bagachi,» the oligarch or rich class of people who leave the country in times of trouble together with their children. «They went to the USA, Britain, while the lower and the middle class have to go to war.» Still, the woman says if the war breaks out, she is going to act accordingly: «I will go after my son to the war, carrying a bag with food for him» – she adds.

Read more: «Zelenskiy: They Are Attacking Our Nerves, Not Our Land»

Find more stories about the Russia’s threats at our Defending Ukraine page.

By Joe Lindsley (follow on Instagram or LinkedIn) and Vitalii Holich, with Kateryna Bortniak

By Joe Lindsley (follow on Instagram or LinkedIn) and Vitalii Holich, with Kateryna Bortniak

Follow Lviv Now on Facebook and Instagram. To receive our weekly email digest of stories, please follow us on Substack.

Lviv Now is an English-language website for Lviv, Ukraine’s «tech-friendly cultural hub.» It is produced by Tvoe Misto («Your City») media-hub, which also hosts regular problem-solving public forums to benefit the city and its people.