[For urgent updates please follow Ukrainian Freedom News on Telegram]

«Only a nation that is free and self-aware can create its own economic institutions»

Kost Levytskyi

To this day, a legend about the sculptures on the former bank building on Kopernika street lives on in Lviv. Oversaturation, Wonder and Irony next to Pride – the primordial companion of all financiers – were supposed to remind the owner of the bank across the street about his brother, whom he refused to grant a loan. Still, this is just a legend.

The first mentions of banking-type institutions in Lviv date back to the 16th century. However, since princely times, as it was in other cities of Europe, one could receive money from moneylenders with interest. They were usually Jews because only their religion officially allowed them to practice such a craft.

The Money Lender. Auguste Charpentier, 1842

Christianity considered any loans at interest a sin. Nevertheless, almost 400 years ago, the Lviv clergy was already thinking about establishing their own pawnshop. It was supposed to give a poor man the opportunity to make a profit from his small savings.

In the article «Mons Pius», which can be considered one of the first attempts to analyze the history of banking in Lviv at the beginning of the 20th century, Franciszek Yavorskyi notes: «Such simple and well-known financial relations in ancient times also had a theological basis, due to which financial interests had to be under the care of the church. What any bank is doing now was once grown to the size of the montis pietatis – the mountain of piety that rose in cemeteries, in the shade of churches, and under spiritual protection.»

In those days, the need for a profitable loan was more urgent than the reward for observing the canonical precepts after death. Even the church authorities understood this. Therefore, in order to protect its own flock from dependence on money lenders, the authorities of medieval Lviv opened the Lviv pawnshop next to the Latin cathedral in the city centre.

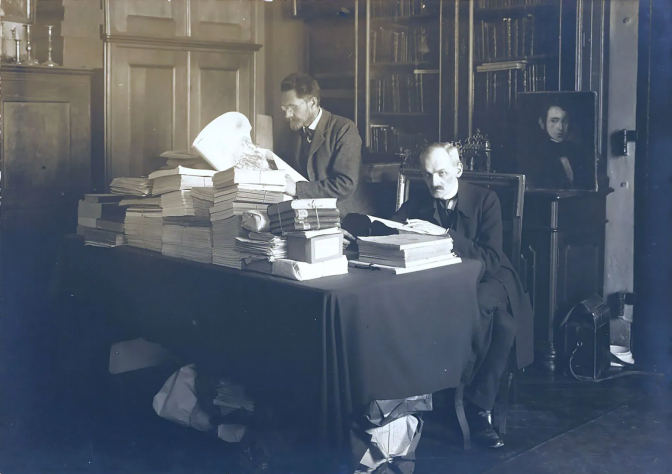

Franciszek Yavorsky and Franz Kovalyshyn in the Lviv city archive, 1911.

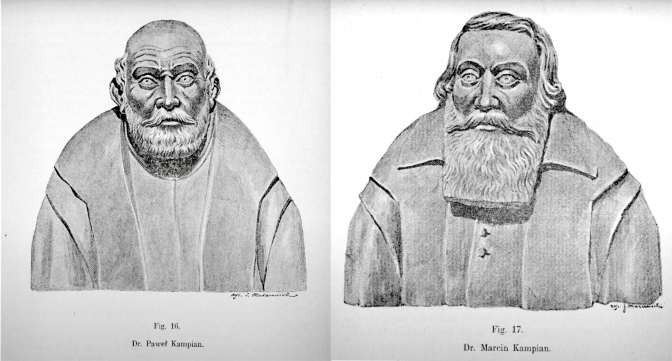

Pavlo and Martyn Kampian can be considered the fathers of banking in Lviv, these were people quite distant from philanthropic thoughts and the desire to help the needy.

Pavlo Kampian, a physician and merchant, was known among Lviv residents as a man of a complicated character. The son was also worthy of his father – Martyn, who was distinguished by despotism, relentlessness and mercilessness towards his debtors, «a real trouble for peasants from suburban villages, a merchant with a sober calculation, a large-scale financier, power-hungry and intolerant of any disputes.» Martyn Kampian, then the burgomaster of Lviv, was considered by his contemporaries to be «a dictator who was not afraid to oppose the city and church authorities during the plague epidemic.»

Pavlo and Martyn Kampian

Before his death, Pavlo Kampian bequeathed 1,000 gold coins to the Lviv Credit Bank. His efforts were supported by wealthy Lviv residents. Thanks to this, Martyn Kampian collected 35 thousand gold coins (an astronomical sum at that time) and used them to improve his father’s endeavours.

In 1627, Kampian the Younger appealed to the Lviv city council with a request to allocate a place for the construction of the city’s pawnshop. According to archival documents, a commission consisting of advisers Erasmus Sixtus, Martyn Korchenivskyi, Jan Alnpek and Mykola Semeratsky, together with the clergy of the city, allocated a place on the southern side of the cemetery next to the cathedral. Death did not allow Kampian to complete his plan, but the institution entered city life and began to provide significant assistance to the townspeople, despite the fact that it didn’t have its own building.

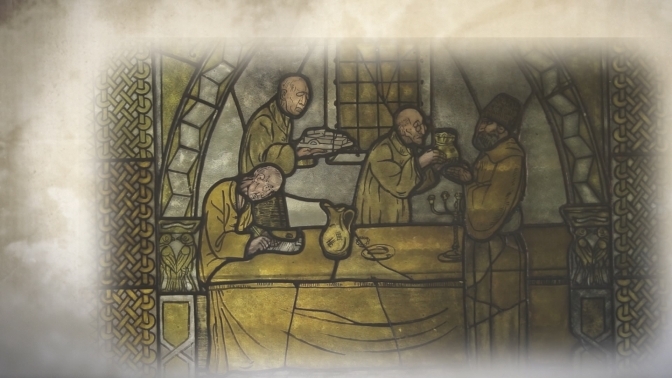

Stained glass from Mons Pius. The scene depicts the working moment of a pawnshop

The military disaster of the 17th century caused the decline of the pawnshop. The rest of the capital and pledged funds passed to the heirs of the Kampians – Martyn Grosvaier, and later to the poet, burgomaster and well-known Lviv historian Bartolomei Zymorovych, thanks to whose efforts this financial institution was reorganised. In 1668, Lviv Archbishop Jan Tarnavsky approved the charter, after which the institution became the exclusive property of the clergy.

Tarnavsky allocated a place for a pawnshop next to the sacristy of the cathedral, assigning for this purpose «sklep murowany» on the territory of the cemetery. The institution was served by two employees who were to be chosen from among the cathedral canons. The position of «prosecutor» or «notary», which today would be called a director, was usually held by a representative of the Kampian family.

Loans in pawnshops were granted against gold, silver, works of art, and clothes – with the exception of fur, as it was very expensive to protect from moths. The term for redeeming the pledge was half a year, and the largest loan that could be obtained was not to exceed the quota of 100 gold coins. Such restrictions were established in order to confirm the philanthropic nature of the bank. A rather low percentage was set for the same purpose. Money could be taken at only 4%, while loans below 50 gold were completely interest-free.

The Moneychanger. Quentin Massys, 1514

According to the regulations, wealthy people were forbidden to use the services of this charitable institution under the threat of legal liability. All profits, taking into account administrative costs, were to be divided between poor women and widows. The responsibilities of the control body were entrusted to craft shops.

If the collateral was not redeemed within the specified period, it was sold. For this, a corresponding announcement was posted on the door of the department.

In 1703, during the Swedish invasion, the bank was forced to evacuate from Lviv. For a long time, even the Lviv church authorities did not have information about its whereabouts. Archbishop Konstantyn Zelinsky, leaving the city, took all the cash with him and left the valuables to Dlugosh, the Canon. Only in 1706, Zelinsky reported that the bank was taken to Prussia together with all the jewels and everything was safe. This did not console the depositors, as it became known about the personal threat to the archbishop from Russian tsar Peter the First. The fears came true, and soon Zelinsky was arrested.

Engraving made by Abraham Hogenberg (nee Abraham Hogenberg) based on a drawing of a Lviv panorama from the end of the 16th to the beginning of the 17th centuries. The work was conducted by Aurelio Passarotti, the engineer of the fortification of King Sigismund III Vasa (1587-1632).

After receiving the news about the archbishop’s arrest, Dlugosh had to present documents about the bank’s financial condition to the city authorities. An analysis of the records, which have been conducted since 1695, showed that the capital of the bank counted 16 thousand gold coins in pledges and cash. It’s interesting that the main client of the bank, which was primarily supposed to serve the poor, was... Zelinsky himself, whose loan amounted to 8,600 gold coins. The rest of the funds belonged to the nobility, priests and rich townspeople. Among the pawned items were glasses, rings, furniture, etc. Cash was only 16 gold coins.

The clergy of Lviv, not hoping for the return of the bank’s property to the city, managed to enter the accounts into the Act books. In this way, it later tried to ensure that the bank and its property belonged to the city. Thanks to this, modern history researchers have confirmation of the existence of banking in Lviv in the 17th and 18th centuries.

After long journeys, to the great joy of depositors, the bank returned to Lviv in 1709. And from that time until 1761, it calmly performed his functions, until a dispute arose between Archbishop Sirakovsky and the magistrate about its affiliation. It’s not known how it would’ve ended if Lviv had not come under Austrian rule in 1772. This led to the complete and final decline of the first Lviv bank.

The first part of the topic can be read here: Galician Wall Street, or the beginning of banking in Lviv.

Translated by Vitalii Holich

The author’s column is a reflection of the author’s subjective position. The editors of Tvoe Misto do not always share the opinions expressed in the columns, and are ready to give those who disagree the opportunity for a reasoned answer.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Lviv Now is an English-language website for Lviv, Ukraine’s «tech-friendly cultural hub.» It is produced by Tvoe Misto («Your City») media-hub, which also hosts regular problem-solving public forums to benefit the city and its people.