[For daily insights from throughout Ukraine, follow Ukrainian Freedom News on Telegram]

The struggle of Ukrainians for their statehood has been going on for more than a century. In the 1960s, during the period of temporary weakening of communist totalitarianism, it united representatives of the intelligentsia, called the shistdesiatnyky, who spoke in defence of language, culture, and freedom of creativity. Writers and poets Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, Vasyl Symonenko, Vasyl Stus, Lina Kostenko, artist Alla Gorska, literary critics Ivan Dzyuba, Yevhen Sverstyuk, director Les Tanyuk, and others formed the basis of the movement.

The participation also got the bright representatives of the national liberation movement Vyacheslav Chornovil, Levko Lukyanenko, and Semen Gluzman. However, even such non-violent opposition to the regime was unacceptable in Soviet times – the authorities quickly blocked all opportunities for activities of the shistdesiatnyky and began a wave of arrests. Nowadays, the representatives of this movement are hardly discussed, although their contribution to the struggle for Ukraine’s independence is difficult to overestimate.

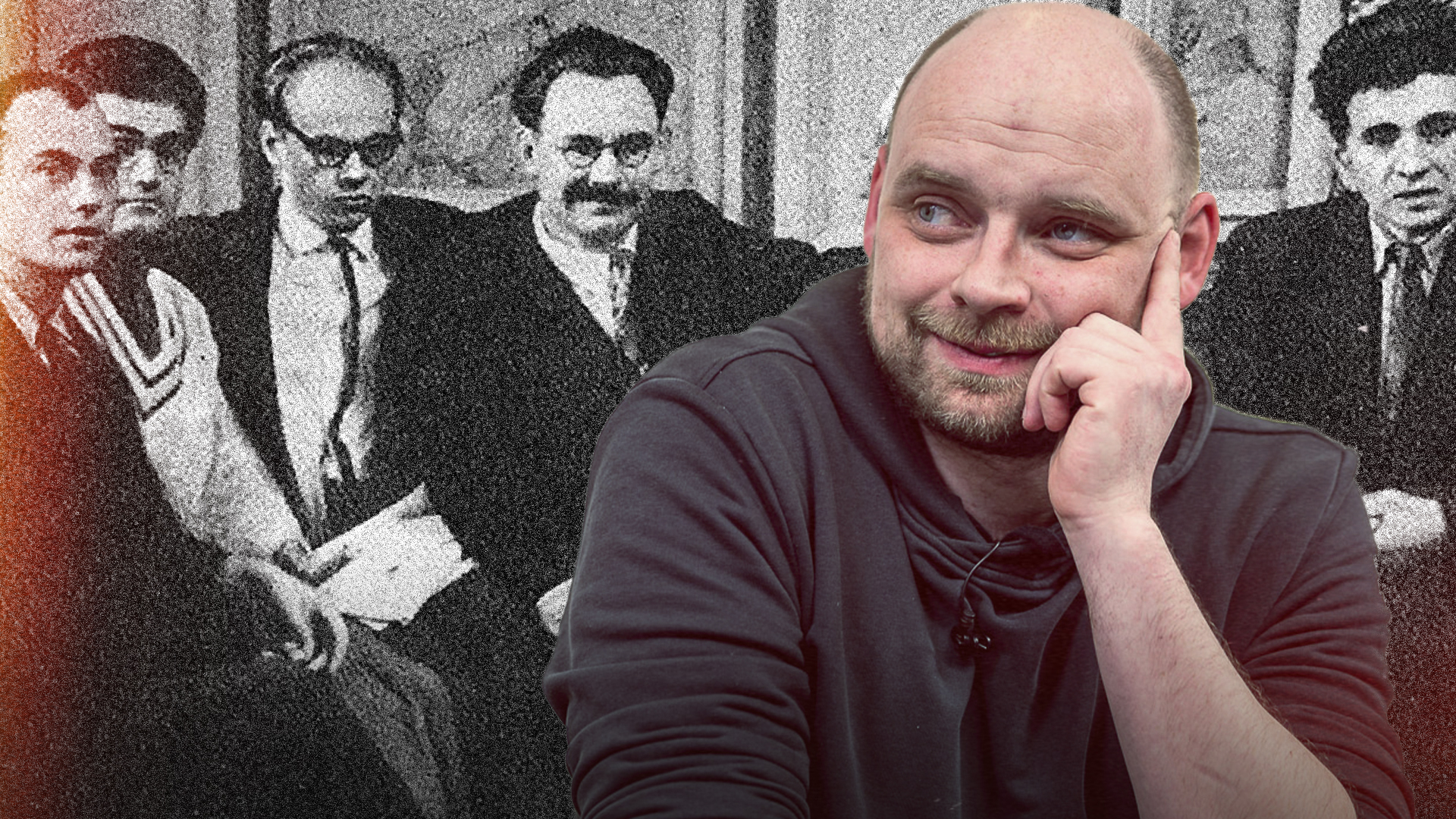

Today, our guest is Radomir Mokryk, a historian, teacher at Charles University in Prague. Now, he teaches there remotely because since the beginning of the war, he left Prague and returned to Lviv. He also teaches here at the Ukrainian Catholic University. We have a good opportunity to meet: his book was printed out, and we can’t even show it (Laughs).

Because it was sold in a week, the second edition is now in print, and I hope soon it will be possible to pre-order again.

The book’s name is «Rebellion Against the Empire: Ukrainian Sixties». It is dedicated to Soviet-era dissidents. For you, the sixties are more historical figures than writers or cultural figures, right?

We can consider it in different ways. The problem is that people in our sixties are often perceived very simplistically and flatly. These are several poems on posters, general ideas about dissidents, and fighters for independence. We use some clichés, but no one understands what it was. Without a doubt, they are real fighters for freedom. It was the stage of the liberation struggle, and I tried to understand them a little as people. I keep repeating that for me, the history of the shistdesiatnyky is the history of the victory of critical thinking. These are people who, being in the vacuum of Soviet propaganda, managed to push all the boundaries and realize that it doesn’t work. As for me, it is of great relevance today.

The shistdesiatnyky were mostly nationally oriented, but they are different. There is Gluzman, who came to all this a little from the side. If we talk about the shistdesiatnyky, was it primarily a national movement or still a moral one?

Very good question. For me, the shistdesiatnyky is primarily an ethical protest. They positioned themselves that way. That is, all dissidence is one way, or another based on ethics, on the fact that you follow your convictions based on universal human values. And in the Soviet system, this almost automatically turns into political opposition. So the basis is undoubtedly ethical. However, the national nerve was very pronounced there from the very beginning. You mentioned Gluzman. I can tell another story. Leonid Plyusch is a completely Russian-speaking person who, joining the dissident circles, did not perceive the national problem very acutely, in his memoirs, he describes a very simple situation. At some point, Ivan Dzyuba’s famous essay «Internationalism or Russification» came into his hands. He reads, thinks, and says: «Okay, I’ll try»...

...I will try to switch to Ukrainian.

Yes. In the experimental mode, he goes to the library and asks for a book in the Ukrainian language. In response, he hears this sacramental: «Can you speak humanly?» And Plyusch says: «I instantly became a Ukrainian nationalist.» That is, this national problem in the Ukrainian Sixties, in Ukrainian dissidence was pivotal. Even if very different people joined, the national motive was very important there.

Nowadays you can often hear that Russian-speaking or Russian-cultured people in Ukraine are in the minority. Accordingly, they are subject to all these things about minorities who need special rights, including the right to speak Russian. But I am not sure that Ukrainians, who were a minority for a long time, in the role of some aborigines, colonized Indians, sent to a cultural reservation, suddenly became some kind of hegemon.

I bring you to the story about the new minister of education, who has already managed to get into a language scandal. At first, he said a rather innocent phrase and condemned the affair with the Russian-speaking teacher.

In Irpin.

Yes. And then, he did not stop, as liberal and progressive representatives of humanity believe. He said that the teacher who speaks Russian during the break seems to undermine everything she said in class. I understand it, but I’m not sure that all Ukrainians at one point suddenly became these white cisgender men – all in a row, even women, and everyone else suddenly turned into some kind of mutilated Indians from the reservation. In addition, all of them are with different minority communities.

Of course, it is a very multifaceted issue. It seems to me that here the perception of the majority-minority is a little distorted, as well as the fact that Russian speakers suddenly found themselves in the minority. It seems to me that they have always been in the minority, just too many Ukrainians were bilingual or switched from their language to Russian. And there are simple reasons for this. It is very important to understand them when comparisons made with other states where several languages function. In the case of Ukraine, it does not work because this distorted language situation is a colonial trauma, a legacy of the empire, and a purposeful policy of squeezing out the language, which carried out not only in the Russian Empire but also in the Soviet period. At that time, everything set up so that many people switched, for one reason or another, and chose the Russian language instead of Ukrainian. Therefore, it is quite difficult to understand what this language situation is.

But the survey results show that 86 per cent call Ukrainian their native language, and more than half speak it every day. However, I always have doubts about the truthfulness of the answers. It seems to me that Ukrainians want to look a little better than they are.

Maybe. This legacy of inertia will exist for some time, some smaller and larger outbreaks of linguistic discussions will occur. But the rhetoric about someone hurting someone else is not serious. Let’s look at the same language law adopted in 2019 from a legislative point of view. If you leave aside the hysteria and read it – then, in my opinion, it is liberal, aimed at ensuring that a Ukrainian-speaking person, a Ukrainian in Ukraine, is not forced to communicate in Russian. So he can speak in his own language.

It also applies to those who come to the villages on the border with Hungary and forced to speak Russian only because no one wants to understand them in Ukrainian. They don’t understand English there either, or they don’t know Hungarian.

Myths about what is prohibited are growing around this. I observed this in the Czech Republic, how someone writes articles about the fact that the Russian language has banned. Don’t worry, no one forbids you to communicate in Russian, just read the law! These are propagandistic clichés spread by those who benefit from it. Let’s not point the finger at the northeast. But this has nothing to do with reality. Go out on the streets of Kyiv and say whatever you want.

However, there is such a narrative and one of its expressive voices is Volodymyr Dubynyanskyi, which often published by «Ukrainian Pravda». He describes these processes. What Oksen Lisovyi calls an opportunity to punish unpunished evil, Dubynyanskyi calls resentment. What do you think about it? Is he right who says that this is such a slightly dormant Ukrainian resentment?

I don’t see resentment here, because I don’t see any hard pressure. If we were really talking about some kind of repressive measures that are taking place because you speak Russian, then you can start to think that maybe someone is bending the stick here.

We recently discussed the situation at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Those many beliefs that Russian speakers are being «oppressed» here cited this as an example. But in my understanding, a university, especially one like the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, is not just about lectures, but community, values. It has the right to cultivate its ideas. It forms a worldview. And this is much more than simply coming, reading lectures, and forgetting. Kyiv-Mohyla Academy decides to issue an order on communication in the Ukrainian language. It articulates some of its values. Moreover, it does not provide for sanctions. And again, we return to the fact that if you speak Russian, you will not get anything for it. But an assured position has been declared: our university, our academy contributes to the formation of such and such values. It is downright legitimate. I don’t see any resentment here, especially since it is only the cultivation of the Ukrainian language and culture in the Ukrainian state. Where are the problems?

Since you connected to Prague, I read your posts where you mentioned Vaclav Havel, so I am very interested to talking about it. Havel led the country after it became free, becoming one of the Soviet dissidents. If we consider this movement primarily as ethical, so we understand that these people deserve to be called moral authorities. After this communist government was completely dishonored and untrustworthy. Why didn’t dissidents become such moral authorities in Ukraine? Why didn’t we have our Havel? Did he exist, but did not become so?

He is probably read somewhere in the person of Vyacheslav Chornovil, who did not achieve such success as Walesa in Poland or Havel in Czechoslovakia. I don’t have a definite answer to this question. We can say that the Soviet tradition was much more firmly rooted here, and regions in the west of Ukraine, where there was a generation less Soviet, still voted for Chornovil. Generally, it is a big puzzle, which I am unlikely to put together here. But I agree.

Somehow it happened at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. The dissidents and the shistdesyatnyky got caught in a whirlwind of criticism. I specifically pulled out some archival articles, and publications of that time and saw that in the 1990s, a narrative was being formed that the shistdesyatnyky did something incomplete, did not finish, and did not hand over such Ukraine. It is a huge problem that causes a crisis of values. We did not take over the values from the best ones and go further into the dragging post-communism instead of changing it more radically.

I understand that there is a mundane level of this problem, which has been discussed a hundred million times. They say, if in 1991, 1st December, Chornovil was elected [a President of] our country instead of Kravchuk, it would have been a completely different story, but it was impossible. It is understandable that was no such society that could vote for Chornovil to give him that 51 per cent. I was still in school then. But I was already involved in voting commissions. We tried to count everything and make sure that there were no falsifications. I’m talking about something else here – is memory considerable? Will Chornovil, in the end, be among those who can be called the founders of this state? This will also mean that there are some ideals with which they came out and became part of this state, the framework in which this state is being built... I hope this is so because we have three revolutions and a war with the Russians. What if not?

We have big memory problems. And the case of the dissidents is very revealing in this. Undoubtedly, it is crucial what is evaluated but not reflected on. But we are not even talking about that. Even a mundane, simplest thing can be: there are only a few dozen of these dissidents, and not only the more famous ones, such as Myroslav Marynovych. And the law on increasing their pensions, which was supposed to be adopted 30 years ago, has still not been adopted. Okay, let’s get moving now, there is a bill by Volodymyr Vyatrovych, which has been in the committee for more than a month. This is a very simple but very practical thing. I communicate with these dissidents; I see that many of them live in very modest conditions. Even these few thousand hryvnias, which would not change the situation radically, are now important. This is the mirror of memory. The state does not have the political will to make even such a gesture to these people, although they deserve much more.

Darka Hirna very often writes such stories. They merely go through. Some dissidents can now live on a tiny pension and make ends meet, and those who wrote denunciations against them were their judges and pseudo-lawyers, like Stus and Medvedchuk...

…They are fine.

Both they and their families. Moreover, they are very often part of the establishment of this country. They inherited this Ukraine and continue to feel like masters in it. What I am saying now can be interpreted as pure resentment. But also, a desire to punish evil to achieve some form of justice.

It is about a crisis of values. The desire to achieve justice, to place the correct emphasis – who was a hero and who was a victim, who was a representative of the repressive apparatus – obviously did not reach the necessary limit for the state to overcome all this. Well, who was supposed to grind it in the 1990s? In the Czech Republic, this is also a long story. It has also been discussed, although they have a completely different start because the dissidents immediately took positions in the government headed by the president. However, if I’m not mistaken, only a year or two ago they passed another law that reduced all allowances and pensions to the representatives of the former StB [State Security of Czechoslovakia] – what we used to be the KGB [State Security Committee of Soviet Union]. They are also still working on it. But they are working straight in the direction you are talking about. We are still «harnessing» this topic, which should resolve a long time ago.

Now I work with students and want to give them an example of a bad journalist who completely discredited himself. It is a definite illustration of the thesis that the fourth power can be just as corrupt as any other branch of government. Of course, I chose the clear figure.

Pikhovshek?

Yes.

Did, I guess? (Laughs)

They watched a short video about him and asked: «Who is this?» And they are sixth-year students pursuing a master’s degree! And they didn’t know who it was! At first, I thought it was very good, but then I said a few words about Sashko Kryvenko...

And they didn’t hear at all...

... 20 years have passed since the day of his tragic death. They didn’t hear the same way. And here it stung me because I thought that Sashko Kryvenko would not rise from the grave, that the memory of him is already very difficult to reanimate. Although it is difficult for me to overestimate his influence, because he molded, as if from the dough, a lot of journalists who later became someone, suffered it all, did not allow freedom of speech to completely twisted here. It didn’t happen here like in Belarus. But Pikhovszek is theoretically the one who can return. It’s easy for me to imagine somewhere at «Breakfast with 1+1» that he comes in a pilot’s jacket, and it turns out he is now a volunteer, helping. He sits down somewhere near Dubinskyi, and they start talking. Therefore, if we do not remember either the first or the second, it is probably not so good.

It is unwell. I am saying that we have serious memory problems. We like to talk about the fact that society quickly forgets political jabs. But it seems to me that this amnesia is much deeper. It is from here that many crises of values arise. It seems, that we still do not have road signs installed. I do not like the concept of «moral authorities», but here I insist that the generation of sixties and dissidents are lessons that we should learn, based on which we could somehow orientate ourselves in life. And this did not happen with us from the word «at all». And this applies to wider circles. It is what you say about Pikhovshek and Kryvenko. You can’t live like a squirrel. You must stick to some guidelines.

I had the opportunity to communicate with Yevhen Sverstyuk. The topic of bread came up, and he said that the worship of bread, the cult of bread exists because we survived the Holodomor. After all, here, in Galicia, there was always terrible poverty among the Ruthenians. They were the poorest, the most marginalized among nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even Ivan Franko wrote about this in his works. Yes, they were probably on a higher level than the people of the Russian Empire, but that’s all-in comparison. And Sverstyuk said that virtually, bread is just bread, there is no point in deifying it. But if someone has said it to me, I wouldn’t have taken it the same way. Something clicked in my head during my years of childhood, «bread is everything’s head», and «Kiss the bread if it falls.» And I suddenly saw through a different lens because it was so. It is a mass of injuries, just a desire to survive, which is passed on to children and grandchildren.

Yes, but we must go through it. All these injuries are also lessons and training. But Mr. Yevhen, certainly cannot be accused of insufficient religiosity. It’s me to whom he says about bread. I think it’s about something else. We must move forward with all this, be able to let our history pass through us and take the necessary lessons from it.

We are back to your original point. It is a lesson in such classical thinking from Yevhen Sverstyuk. Finally, a bit of resentment: I was on Yevgena Sverstyuka Street in Kyiv. I don’t think he did so little for the country that... Something is wrong with that.

I visited Mr. Yevhen’s house very often. Once we were walking along the street, which was then called Raskova Street, I don’t think he would have liked it renamed after him. These people did not work for that. It was about ethics, virtually that «against all the world, I will be true to my convictions.» Because of this, they seem very valuable to me.

But in fact, it is not important here what Sverstyuk thought about this matter. What is important is how we passed on and will pass on his legacy, and his lessons. And this is very few, here are few people in the public space. Although there are tools to spread their thoughts, they have been used for something else. It also indicates a certain crisis of understanding of what is happening.

There is a common joke among historians who study the liberation struggles of the beginning of the 20th century: «If the meeting of the Ukrainian club at the Golden Gate had been arrested, then maybe there would be neither Ukraine nor the Ukrainian revolution.» It is about how small the concentration of people who started the fire, which just a few months later gathered a hundred thousand people in Khreshchatyk. And suddenly, everyone saw where the Ukrainians came from. If we talk about the handful of people who were not afraid and went to prison for their beliefs, were they the ones without whom Ukraine would not exist now?

I am convinced that it is. In addition to the fact that we talked about some lessons, this is also a practical story. Because starting from the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, when Vasyl Symonenko and Ivan Drach wrote when these modernist poems written by Vinhranovskyi, above all Ivan Svitlichnyi, they made this concentrate on Ukrainian identity. Perhaps it was not so visible, but it was on their shoulders that the dissident movement arose, and it was from there that the political opposition went. And if this clot of national culture did not exist...

A few years ago, the former «press secretary» of the current president wrote a post for Independence Day that suddenly there was independence, that we were like a tabula rasa. I was outraged by this. I wrote back that it was total ignorance. This tabula rasa was the death of Stus, 26 years of imprisonment of Levko Lukyanenko, all those decades in the [Soviet] camps spent by Svitlychnyi, Sverstyuk. Behind this stands colossal civic courage and national nerve. And that’s why we weren’t a tabula rasa. It is why it all blew up. Moreover, even from a practical point of view, there have presented many of these people in the parliament at that time – Tanyuk, the Horyn brothers, Lukyanenko, and Chornovil.

…Of which there were a little more than a hundred who broke it all.

111th, if I’m not mistaken. They were still in the minority, but their initiative was extremely important then. If it didn’t happen, then...

There would be no less outrageous words than «What are these two grandpa mopeds?» the current head of the parliamentary faction. But I want to say one «But»: when the spokeswoman of the president at the time said so about it, she was describing her experience.

Yes, but this is about ignorance – nothing more and nothing less. I understand that she was sincere in this. I am convinced that she did not mean anything unwell. I am sure that there are millions of such spokespeople. And here we return to why this happened. Where is our education? Where is our promotion of these people? Where is their recognition at the state level? Where are they in public space, in a single marathon?

I am afraid of something else: it is not ignorance, but simply unwillingness to accept it as our own, to say that we have our alternative.

But this alternative is empty, it is a taboo race, and it does not produce meanings or values. It’s just an idea that somehow everything happened, and now we’re doing something. It is emptiness.

Thanks for the conversation! I hope that the next time the second edition of your book comes out, we can hold it in our hands and continue our conversation.

Translated by Yulian Lahun

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Lviv Now is an English-language website for Lviv, Ukraine’s «tech-friendly cultural hub.» It is produced by Tvoe Misto («Your City») media-hub, which also hosts regular problem-solving public forums to benefit the city and its people.