Soviet occupation and propaganda through cinema

The Soviet government, which established the first occupation regime in the city in 1939, came to Galicia with the idea of liberation from Polish domination. Therefore, Poles became the first victims of Soviet repression.

Each new regime that took over Galicia renamed the urban space in its ideological language. That is why when the Soviet authorities came here, they immediately renamed Svobody Avenue (then Legionów (Legions)/Hetmańska – Tvoemisto.tv) to First of May Avenue. Later, it was renamed Lenin Avenue after the Second World War.

At the same time, powerful propaganda began to spread that the inhabitants of occupied Lviv were happy because they had become citizens of a new progressive young state called the Soviet Union. However, such things kept silent as repressions against certain national groups.

Halyna Vyliika, a guide at the Territory of Terror museum

Innovative methods promoted Soviet propaganda, such as cinematography, which was cutting-edge. In September, before the start of World War II, Lviv had seven movie theaters. Within two months, by November 1939, the number had increased to 25.

According to historical chronicles, films were also imported from abroad. However, the Soviet Union quickly established its own film industry. In 1939, the renowned Ukrainian film director Oleksandr Dovzhenko was invited to Lviv. He arrived in the city with his wife and embarked on the creation of a film that depicted the anniversary celebration of the «reunification of Western Ukrainian lands with the Soviet Union.» The film, titled «Liberation,» was premiered a year later, in September 1940. Its central theme revolved around the idea of brotherhood and friendship among Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians. The film aimed to manipulate this narrative and promote unity among these different ethnic groups.

People’s «referendums,» prisons, and deportations

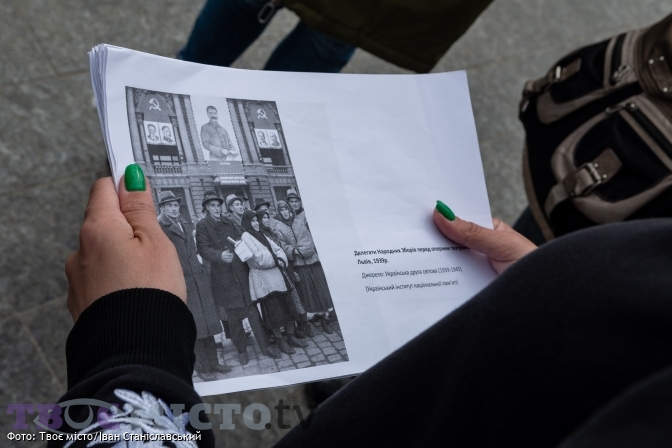

In October 1939, so-called «people’s assembly» was convened at the opera theater. It is similar to what the occupiers did in eastern regions of Ukraine – pseudo-referendums. Staged photos were taken with «peasants» who supposedly expressed their desire to become citizens of the Soviet state. During this so-called assembly, several laws were proclaimed. One of them included provisions for nationalization, Sovietization, and collectivization. According to this law, all private property was supposed to be transferred to state ownership. Anyone who resisted was considered a criminal and could be arrested and deported to Siberia.

Delegates of the so-called people’s assembly in front of the Lviv Opera House. Approximately 1939.

Aleksandr Loktionov’s painting «Moving to a New Apartment» clearly illustrates that period because the people who did not agree with the nationalization were arrested and deported. Their apartments became places where the so-called new tenants, the «owners,» were resettled.

Ukrainians who were young at the time told our museum about the evictions, for example, Mykhailo Bachynskyi. The government deported his family because they did not succumb to pressure.

«The Red Commissar came and said that we would go to my dad. They had already arrested him. Mum did not take a spoon or a fork, nothing. She thought they would shoot us. There was no other thought. We didn’t take anything. The only thing left was what the Soviet officer threw on the sled. And I, like a boy, took a Bumblebee, a book, and a Gospel book. I don’t know how I got it, but I have it. Maybe my mother took it. I don’t remember. I also took a pack of pencils and a bunch of notebooks. Later, in Kazakhstan, I went to sell them and exchange them for bread – it was currency,» Mykhailo Bachynskyi recalls.

We can draw analogies, and, incredibly, people are evacuating from the war zone today and taking their most valuable belongings. Someone comes with a small backpack, and that’s it. And for someone, it was a violin, a book, pencils, and notebooks.

Monument to the victims of political repression

All nationalities in Galicia suffered equally from the Soviet occupation. All citizens were arrested, charged with crimes, subjected to «trials,» and deported. They nationalized property, evicted people, and ultimately executed Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians. The intellectual elite, priests, and owners of small enterprises became targets for annihilation.

Initially, they took them to prisons where so-called interrogations took place. They built cases, and only then were their trials. We had four such prisons: three large ones and one execution chamber. These included the prisons on Lontskoho (Łącki) Street and Horodotska Street (Bryhidky). Once there was the Monastery of St. Bridget, which was converted into a prison during the imperial suppression in Austria. In essence, it continues to function to this day, but as a pretrial detention center. The third prison was located in Zamarstyniv.

Soviet executions in Lviv

At the beginning of summer in 1941, when it became evident that the Germans would declare war on the Soviet Union, the Soviet authorities began evacuating from the region. Instead of resisting the Germans in western Ukraine, they intended to retreat. However, the prisons throughout Galicia were filled with individuals whom they considered criminals and potential collaborators with the hostile authorities. The Soviet authorities saw no alternative but to execute them.

On June 22, 1941, Germany declared war on the Soviet Union, and the first air raids began. Lviv came under bombardment. The Soviet authorities had little time to escape from the city. Within a week, they eliminated all the political «criminals.» In the initial days, they lined them up in rows in the courtyards and executed them. Later on, they simply threw grenades into the cells. During the two years of Soviet occupation, approximately 200,000 people were arrested and deported. Around seven thousand were executed in a matter of days in June 1941. Only in the prison on Lontskoho Street, the remains of a thousand people were found. Excavations and reburials are still being conducted to this day. It was a tremendous crime.

German occupation and pogroms

On June 30, 1941, Nazi Germany, the new occupier, entered Lviv, bringing along its propaganda. They opened the gates of prisons and invited the townspeople to come and witness and claim the bodies of their loved ones. They accused the Jews of the collaboration with the Soviet authorities, omitting any mention of their victimization under Soviet terror. The Jews were portrayed as traitors and collaborators who carried out the criminal orders of the Soviet regime.

The Jews of Galicia proclaimed themselves neutral and were more concerned with their education and well-being. But this position was one of the reasons that made them victims. It was used by the regimes for propaganda, to mock them.

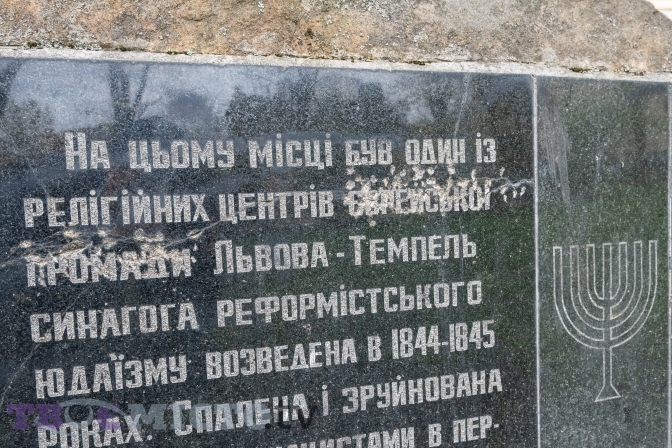

A memorial sign on the site of the former synagogue

The Nazis labeled Jews as communists. As a result, a dark chapter in history unfolded, known as the «pogrom,» which took place in Lviv for three days in July 1941. Ukrainians and Poles launched attacks against Jews on the streets of Lviv. They hunted them down in their homes, dragged them to prisons, and forced them to unearth and retrieve the remains of those killed there for reburial at the Yanivsky Cemetery. The Nazi occupation authorities fueled this violence. One of the degrading methods imposed on the Jewish population was the forced cleaning of pavements.

Urbicide

Around the same time, the Gestapo launched a campaign to destroy the landmarks used by the Jewish population. Synagogues, in particular, were targeted for destruction. The largest synagogue in Lviv, known as the Temple, belonged to the Reform Jews and was situated in the Old Market Square. This magnificent synagogue was built by prominent Lviv architects in the mid-19th century. Unfortunately, during the summer of 1941, it was demolished along with numerous other synagogues. The city lost nearly a hundred synagogues in total.

In Lviv, there were a total of 150 synagogues, along with 50 private prayer rooms located within other buildings. However, due to the Nazi policy of urban destruction, which targeted not only the Jewish population but also the city itself, only four synagogues remained standing. This heartbreaking reality was depicted by Yevhen Nakonechny in his book «The Shoah in Lviv.»

The Judenrat

In August 1941, just two months after the invasion, the Germans announced the establishment of the Judenrat, a Jewish council that was to obey the orders of the Gestapo. This practice was implemented in many occupied cities, including Krakow and Warsaw. It was one of the methods used to degrade and manipulate the Jewish population. People believed that working for the Judenrat would ensure their survival, but in reality, they were among the last to be executed.

A building on the territory of the former ghetto where the Judenrat was located

During the first year of the establishment of the Judenrat, there were initially around one thousand employees, which increased to five thousand within a year. One of its departments was the Jewish police, which operated alongside Ukrainian and Polish police forces. All of these police forces were involved in committing crimes against the Jewish population.

Ghetto

They divided the city into a ghetto around the Pidzamche district, a public part, the center where Ukrainians and Poles lived, and a governmental «Aryan» part on the present-day streets of Konovalets, Chuprynky, and Heroiv Maidanu. Germans inhabited the latter area.

In the first six months, Jews were free to move around Lviv, but new orders appeared every week. In particular, Nazis forbid Jews from using pharmacies or visiting coffee shops. They were not allowed to walk on sidewalks, only on the roadway, and were obliged to wear a Star of David on their left arm.

The ghetto was established in November 1941. In two months, absolutely all Jews had to move there. There were approximately 110,000 Jews among the townspeople before the war and up to 50,000 Jewish refugees who fled from the German offensive against Poland to Lviv.

The Hadashim Synagogue is one of the two remaining synagogues in Lviv

Some of them were deported to Siberia by the Soviet authorities, but about 120-130 thousand remained in Lviv. The Nazis resettled them in Pidzamche district. The main gate there was on Zamarstynivska Street. Two other gates were on what is now Dzherelna and Chornovola, then Pełtewna. But in fact, the resettlements took a year.

In the ghetto, each Jew had only two square meters of space. Initially, every individual was required to work. The Nazis propagated the belief that if you didn’t work, you had no right to live. This led to the establishment of a forced labor camp, where German enterprises were involved in clothing production, tailoring, manufacturing uniforms, devices, weapons, and ammunition. The main center was located on Shevchenko Street (formerly known as Yanivska Street). It housed a camp that later became known as the Yanivska (Janowska) Camp. Every day, Jews were forced to commute there for work.

They were required to obtain work permits, which needed additional stamps to be renewed every few weeks. Exiting the ghetto boundaries was not allowed unless it was for work purposes. If the Jewish police checked the documents and found missing or incorrect stamps, the person would be immediately arrested.

In the ghetto, Jews were «selected» – separated into the able-bodied and the disabled. Young children, people with disabilities, and the elderly were kept in the Jan Sobieski school. Later, they were packed into wagons and sent to the Bełżec death camp. In the first few weeks, the Nazis killed nearly 12,000 people.

On the territory of the former ghetto

Initially, Nazis believed Jews would be brought to the labor camp from the ghetto and then returned. But the Germans realized that this would require significant resources, and they forced the same Jews to build barracks in the camp. At first, it was a forced labor camp, then a ghetto, and then a transfer point to Klepariv station, where Jews were transported to Bełżec (in 1943, it became a death camp and no longer accepted anyone – Tvoemisto.tv) They created a sand quarry nearby for mass executions.

Janowska camp

Approximately 80% of Lviv’s Jews were deported to the Bełżec and Sobibor death camps. Another 20% were murdered in Lviv itself. Only a small percentage, around 2%, managed to survive the Holocaust, amounting to one to two thousand individuals.

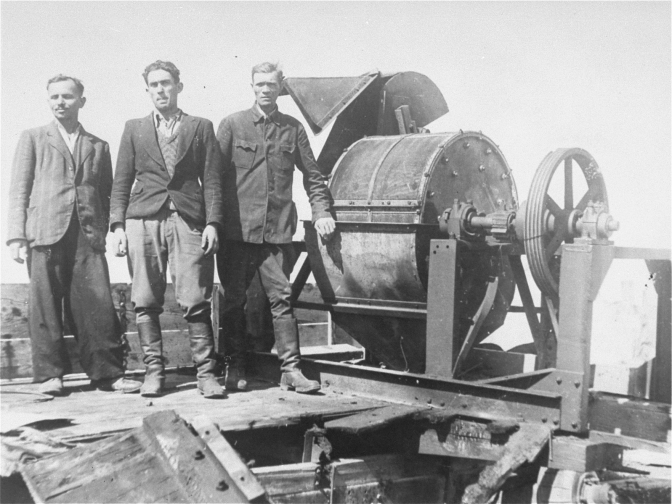

Friedrich Wartzok, Fritz Katzmann and Heinrich Himmler in the Janowska camp

It is impossible to say how many people Nazis tortured in the Janowska camp. In 1943, the Germans declared Lviv free of Jews and began to eliminate evidence of their crimes. The Polish and Ukrainian police, and the Sonderkommando, exhumed bodies from mass graves and destroyed them with stone crushers (a stone crusher from Lviv is now on display at the Museum of the Second World War in Kyiv – Tvoemisto.tv)

Germans executed approximately 35,000 people in Lviv in the sands near the Janowska camp. They did not spare even employees of the Judenrat and the Jewish police; they shot them the last.

A bone grinding machine in the Janowska camp

It was impossible to carry out a rebellion. Each uprising was accompanied by mass executions. For one killed German, the Nazis hanged many Jewish police officers.

Life underground in the sewers of Poltva

Every year the ghetto’s territory shrank, and in 1943 it was called the Judenlager, a Jewish camp. Each barrack had its name, where specific employees of specific enterprises worked. In total, there were several dozen barracks. The Territory of Terror museum is near them.

Krystyna Chiger, one of the survivors, wrote the book The Girl in the Green Sweater. The Chiger family moved to Judenlager from a spacious apartment on Copernicus Street in 1941. In 1943, when the Germans reduced the ghetto area to 14 barracks, they spent a week digging a tunnel to Poltva with spoons under the barracks out of desperation. They made a 50-centimeter hole in a concrete sewer, and 50-70 people escaped the camp.

They came across a utility worker who agreed to take 21 people. Among them was the Chiger family.

The Jews hid under a manhole near the church of Our Lady of the Snows and under a sewer hatch near the church of St Andrew. They stayed underground for 14 months without good food, air, or water. Every day, one of the men would crawl underground, holding a kettle in his teeth, to the fountain under Rynok Square – to Neptune. He would take as much water as the kettle could hold.

The hatch under which Jews lived for 14 months in Lviv

Krystyna Chiger, the author of a book, is one of those who survived the Holocaust, wearing a green sweater throughout that time. In 2006, she visited Lviv and had a presentation at the Center for Urban History. In 2018, an underground route was presented, which was used by Jews as an escape route during the Holocaust.

The new Soviet occupation and the continuation of crimes

In 1944, the Soviet authorities established Transit Camp No. 25 on the site of the former Judenlager, which served as a prison for those who were deported to Siberia. Repression continued here until 1955. Therefore, we are talking about victims not only during the German period but also during the Soviet era. One of the cattle cars used to transport people to Siberia is still among the exhibits.

Monument to the victims of the Lviv ghetto

Translated by Yulian Lahun

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Lviv Now is an English-language website for Lviv, Ukraine’s «tech-friendly cultural hub.» It is produced by Tvoe Misto («Your City») media hub, which hosts regular problem-solving public forums to benefit the city and its people.