A Ukrainian soldier receives communion in the Greek Catholic Garrison Temple, a church dedicated to the military, in Lviv, western Ukraine, 1,300 km (800 miles) from the currently Russian-occupied territories in eastern Ukrainian.

Analysis by Joe Lindsley

LVIV, UKRAINE – For the second time in 2021, words and headlines from afar strengthen the rumors here of a Russian invasion. Yet on the ground, I, an American journalist mentored by people who helped start the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, see a different picture: a vibrant, creative, industrious nation, where people are not especially worried, because – fact is – Russia has already been invading Ukraine for the past seven years.

Each new threat of invasion, however baseless, succeeds in one way: It scares people and money away from Ukraine.

Since 2014, Moscow has directly controlled Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula while also supporting separatist efforts in Donbas, the temporarily-occupied territories in Ukraine’s far east. Over the course of seven years, at least 4,740 Ukrainians have died in the fighting during those seven years. Those sacrifices are recalled often here in the far west, this city 70 km (43 miles) from the Polish border: At the city’s Garrison Church, I see people of all ages praying before the memorials.

But the overall mood in this nation of some 40 million is a bemused confidence, even in the pandemic. Some small businesses have shuttered, of course, but others pop up in their place, while others use their tech know-how to innovate (Ukrainians are among the most energetic adopters of bitcoin). The streets are full of music and singing and unlike in much of the world in 2021, Ukraine’s cities hosted many cultural, culinary, and music festivals here: jazz fests, «Coffee, Books, and Vintage Fest,» «Craft Beer and Vinvyl Music Festival,» IT Arena tech fest, etc.

Read more: The Best Wisdom from Lviv’s Annual IT Arena Tech Festival

Outside of the territories occupied by Russia-supported forces, Ukraine is a safe, peaceful nation, with little of the violence so common in American cities, and strong traditions of community, tolerance, and family.

Then, the bubble began to burst, thanks to that news from afar: Three weeks ago, a friend who previously worked at a high level in the United States government on security matters wrote me from the USA: «Stay safe brother. Let me know if you need a quick exit.» The pace of such messages from various people began to increase. On 4 December the Washington Post reported, from American intelligence, detailed strategies for a possible Russian invasion in January.

I was at my barber shop when a Ukrainian woman sitting next to me told the room that news. The Ukrainians shrugged it off but the foreigner there, a German, was concerned.

And suddenly, all the momentum I have witnessed building for Ukraine stalled.

The Rynok (Market) Square in Lviv

Lauren Spohn, an American Rhodes Scholar, at the University of Oxford, had visited Lviv and Ukraine’s Carpathian mountains in October. Captivated by the creative spirit of the people, she wrote an essay for Lviv Now about what she called the Lviv Life: «great wine, stellar jazz, free conversation, and most of all, good people.» Lviv, she wrote, is a place Americans come to searching for ideas.

Her article inspired a group of Americans to plan to travel here for «eastern-calender» Ukrainian Christmas, 7 January, but then fears of Russian gave people pause. A musician I know from Ohio aso planned to come here in January for a music project: «I hope Russia doesn’t ruin my plans.»

Read more: During Ukraine’s January Christmas, an American Finds the Soul of Music.

This is nothing new: In December 2018, I was days away from leading a group of American entrepreneurs on a trek to Sweden and Ukraine when Russia seized two Ukrainian warships in the Sea of Azov. The participants nearly cancelled until security expert friends of ours said everything would be all right in Kyiv, which it was.

But the perception of hazard is powerful. And maybe this is Putin’s strategy.

«In many ways, the way to counter Russia and Russia’s long-standing imperial ambitions is to make Ukraine succeed,» Stanford University’s Francis Fukuyama wrote for the Atlantic Council in 2019. «That’s the single thing Western powers can do that’s going to make a big difference in Ukraine’s struggle.»

And the easiest way to stop Ukraine from succeeding is to make a lot of noise about potential invasion.

Russia’s «main [goal] is to sow despair, anger and hatred, so that we destroy ourselves,» Ostap Kryvdyk, an activist, artist, and political scientist at the Ukrainian Catholic University Analytical Center, told Lviv Now last month. «Russia would be satisfied with the paralysis of Kyiv and other centers, the power outage of Ukraine, the deprivation of its mobile communications or the Internet. The occupation of Ukraine is not what Russia has the power to do.»

Read more: «The Kremlin Tries to Sow Despair, Anger, and Hatred, So That We Destroy Ourselves.»

Why does Russia continue to make noise about Ukraine? What’s the goal? We can’t know the mind of Putin. Does he, for example, pine for Kyiv, the spiritual heart of the Rus people, a city more ancient than Moscow?

Or is the matter more practical?

«Russia can’t have a free Ukraine,» an American friend in Kyiv told me a few years ago, «because if Russians could see a flourishing Slavic free society where a lot of people speak Russian, they might wonder why not us? Why can’t we be free?»

What is ‘Free Ukraine’?

«In 2014 [at Euromaidan aka the Revolution of Dignity] we literally won,» Serhii Pukhov, a software engineer and punk rocker in Kyiv told me last week. He’s one of a growing number of young Ukrainians from the eastern half of the country who reject the Russian language of their childhood and now, as often as possible, only speak Ukrainian.

«When needed, we stand for ourselves.»

He describes that revolution as a moment as a power: The people peacefully succeeded, the pro-Moscow regime fled to Russia. Alas, as he noted, the people of Belarus and Hong Kong tried but have been unable to achieve this.

A scene in Ukraine’s Carpathian mountains

Read more: «With Winnie the Pooh, Ukrainian Punk Rockers Stand with the Chinese People.»

«Ukrainians are not afraid,» an American friend who has worked to bring investments to Ukraine for years, told me at a wedding on an idyllic island in Kyiv’s Dnipro River last year, attended by many of the Americans and Ukrainians working to keep this country free and vibrant. «That’s the big difference between Americans and Ukrainians right now.»

While the governments of Italy, France, and the United Kingdom, sometimes forced people to stay in their homes during the pandemic, despite business lockdowns here, such house-restriction never happened in Ukraine–perhaps because of the memory of how the people stood in the streets in the freezing winter of 2013-14 until the oppressive pro-Moscow regime fled. You can only push the people so far.

And that revolution gave Ukrainians a new cultural and economic confidence:

«So many people here have such high IQs and work ethics, it’s really amazing,» an American who lives in Switzerland and does business here told me last week, as we sat drinking Ukrainian wine at a café popular with artists and musicians amid the car-free cobbled streets of this western city. Last week I also met two Norwegians who, though their tech company is focused on a Norwegian audience, hire most of their employees from Ukraine. None of these people were making plans to cease operations here.

Ukraine: a country of café society, stunning nature, and vibrant cities

A scene at Lviv’s LV Café jazz club, October 2021

«Lviv is a wonderland,» an advisor to an American billionaire told me when visiting this summer and spending time in the cafés of Lviv’s Virmenska Street with a lively scene of artists, musicians, and writers. Last weekend Lviv hosted a jazz festival, with American and European musicians. The cafés are buzzing with laughter and conversation. Business continues and foreigners still come here, especially from the USA, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, because, as they all invariably tell me, they feel free.

Read more: Lviv Becomes a Center for Tourists from Saudi Arabia

«Ukraine is at a romantic phase, which is why it is so powerful,» Ukrainian impresario Vlad Troitsky, creator of the successful band Dakha Brakha, told The Odessa Review in 2016. Free to forge a new identity, Ukranians are tapping into their roots and finding new ways to develop while giving oxygen and confidence to their ancient culture.

In Summer 2021, Lviv’s musicians gathered at Dzyga music venue to honor the late impresario of their city.

Chornobyl Porn

Prypriat, the abandoned city near Chornobyl

Despite all the vibrancy of actual life here, it is still a popular trope to say how bad Ukraine is.

«The writing is on the wall,» Melinda Haring and Doug Klein wrote in the U.S. publication the National Interest 31 March 2020, just as the pandemic began. «Ukraine is headed for major catastrophe.» Europe’s «poorest country» with a «showman president» is so ill – equipped that soon the Coronavirus will destroy the nation’s economy, they argued.

The prediction did not play out – and the National Interest never issued a follow-up. Granted, these things are hard to document: Not everything can be measured by GDP: There’s a resilience – economy here, with lots of cash stashing, and, besides, most people have relatives in a village who know how to fix things and grow produce. There never was a widespread toilet paper panic or angry public disputes about masks like there was in the USA. As a friend says, Ukraine has «the hidden power of the enlightened third-world society.»

In fact, a growing contingent of foreigners, including Americans – I have spoken to at least a dozen such people in Lviv–began to travel and try to relocate here during the pandemic because they heard it was a more resilient and free place than so many nations during the Covid crisis. Ukrainians, especially after 70 years of Soviet occupation, are survivalists.

Yet the narrative remains of a helpless nation.

In a podcast last week, James David Dickson of the Detroit News and I spoke about «ruin porn» news: For years, national media have visited Detroit to see how bad and abandoned it is, ignoring other stories.

Likewise with Ukraine: So many travel shows – Netflix’s Travels with My Father and the BBC’s Top Gear two examples–come to Ukraine mainly to see the nuclear ghost town of Chornobyl, and, moreover, they visit in winter after all the leaves have fallen and before the snow arrives.

«In other words, the most sh*tty time,» as Zakhar Pikh, a Lviv bartender and cohost of our Speak Freely podcast, said.

You could call this Chornobyl porn, depicting Ukraine as always in some nuclear winter.

Verkhovyna, Carpathian Mountains, September 2021

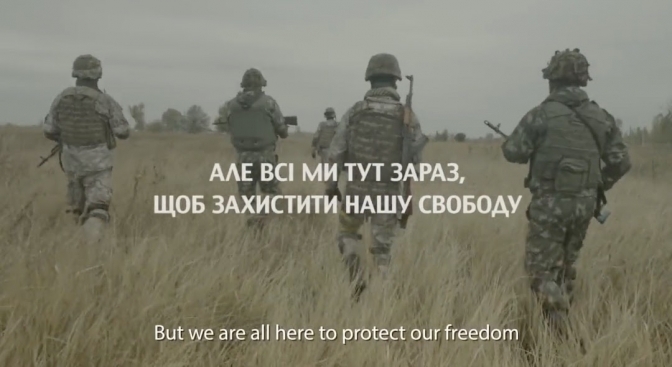

Even those who seem to support Ukraine are eager to focus on the idea of war. Amid the escalating Russia-threat headlines, John Noonan, senior counselor for military & defense affairs with United States Senator Tom Cotton tweeted a Ukrainian army promotional video.

Noonan called it a «deeply effective recruiting video from a free nation about to be invaded by Russia.» A strong emotion. But according to good sources here the video was not from 2021. It was not a response to the latest Russian headlines but rather an earlier response to a long-term ongoing problem, despite which life and business continue here.

Yet the urge to make things seem urgent and dire is strong, and so Noonnan seemed to jump at the chance to portray Ukraine as on the eve of war. His Twitter bio, incidentally, says, «hey no reason this national security stuff can’t be fun.»

Read more: «Lviv Stories. Why Do People Start Wars?»

I began my career working for the people who liked to start wars, so I recognized the sentiment.

Ukraine in the Middle: The Gates of Europe?

One way to measure the value of Ukraine is to look at who is in a sense fighting over what is the largest country wholly within Europe.

«Ukraine is always simply subject of bidding,» a Lviv friend and business owner texted me, after Putin and U.S. president Joe Biden spoke for two hours 7 December about the future of Ukraine.

Why is the fate of an industrious country of 40 million determined by a phone call between the Russian and American presidents? Or by Germany and Russia, in the case of the Nordstream 2 pipeline that will likely cut down on Ukrainian gas exports and make Europe more reliant on Russia?

Amid the past years of turmoil and uncertainty Ukraine has had many cameos in an unfolding multi-national drama, a geopolitical football. It was the setting for a phone call that launched the impeachment of US President Donald Trump. It was the place where Hunter Biden, son of the current US President, made $60,000 a month consulting with the energy firm Burisma.

Ukraine has also been the battleground for US-Chinese competition over a Ukrainian defense contractor, Motor Sich, with highly-prized aircraft engine technology.

And there have been accidental matters: In January 2020 during a moment of great tension with the United States and Israel, Iran shot down a Ukrainian International Airlines passenger jet. Then in the spring, Du Wei, China’s ambassador to Israel was found dead in Tel Aviv. His most recent posting, as of last December, was ambassador to Kyiv, where he had, in an oped, condemned any Ukrainian who stood with the people of Hong Kong.

Another player lurks: Beijing

Kyiv-based activist Arthur Kharytonov, the 20-something leader of Ukraine’s fledgling Liberal Democrats sees, amid all the Russian troubles, the hand of a more powerful regime: Beijing.

Kharytonov has been a China-watcher ever since a visit to Hong Kong several years ago. With his team at the Kyiv-based Free Hong Kong Center, he tracks the moves both of China’s ruling communist party and of Moscow’s activity in Eastern Europe. Witnessing the Hong Kong experience, he now sees Ukraine’s greatest threat as the «red hydra of Russia and China,» two nations increasingly cooperating against the West, and two nations who see Ukraine as the «gates of Europe.»

«China is doing everything to ‘synchronize’ Ukraine within Russia – to revive communist occupation from Hong Kong to Uzhhorod [a western Ukrainian city on the border with Slovakia].»

And while it seems Ukraine is often left out of negotiating its own future, people like Kharytonov, the political activist, and Pukhov, the punk rocker, criticize Ukraine for not standing with oppressed peoples, despite Ukrainian’s long history of oppression at the hands of Moscow.

Read more: «In Ukraine-China Relations, Where Goes the Spirit of Maidan?»

In July 2021 Ukraine unexpectedly withdrew its signature from a Canada-led statement in which 40 nations criticized the Chinese Communist Party’s treatment of the Muslim Uyghur people in Nothwest China.

In response, the aforementioned Pukhov’s band, Dity Inzheneriv («Children of Engineers») released last month a song, «Textbooks,» in support of the Hong Kongers and the Uighur people, whose liberties are restricted by the Communist government in Beijing.

The band Dity Inzheneriv («Children of Engineers»), with the cover art of their single, «Textbooks»: Winnie the Pooh, a symbol forbidden in China because dissidents use it to mock President Xi Jinping, whom they think resembles the chubby cartoon character.

Read more: «With Winnie the Pooh, Ukrainian Punk Rockers Stand with Chinese People.»

What will happen?

Amid this swirling mess of interests and concerns, Ukrainians, even when talking about the threats, sound nonchalant, nearly universally in all of my conversations here – though the nonchalance is noticeably wearing down with week after week of negative headlines.

Perhaps this lack of fear, if we call it that, can lead to complacency about threats.

«As for society in general, it is less prepared for a crisis because people are quite relaxed,» Ostap Kryvdyk told Lviv Now/Tvoe Misto. «Ukrainians do not feel that a potential Russian invasion is an existential threat. Something similar happened in 2014 in the [now-occupied] Donetsk region, when houses were burning there and people had to flee under fire taking nothing with them.»

Or maybe it is a strength:

In the summer, at the lively LV Café jazz club – a place visited in recent months by some of the world’s great musicians including Kamasi Washington and the pianist for Adele – I spoke with Steen Nørlov, a Danish diplomat who leads the Council of Europe’s Kyiv office. He told me there is something special that Ukraine, with its people’s «ability to mobilize,» can teach the world.» The Revolution of Dignity, he said, «reminded everyone what can happen if you don’t listen to the society.»

This could be a power – and also a threat to tyrannical regimes of Moscow and Beijing.

Read more: Sunrise Jams with the Legends: Lviv’s New Musical Moment.

Read more: «No Matter What Happens,» Ukraine Faces West.

Follow Lviv Now on Facebook and Instagram. To receive our weekly email digest of stories, please follow us on Substack.

Joe Lindsley, an American journalist who ended up in Ukraine in pandemic exile, is the editor of Lviv Now. An alumnus of the University of Notre Dame, he formerly was protégé to Fox News chairman Roger Ailes, a position escaped as portrayed in the Showtime show The Loudest Voice. He has also worked for Bill Kristol’s The Weekly Standard and American philanthropist Foster Friess, and he once managed a Celtic-Ukrainian folk rock band. You can follow him on Instagram.

Lviv Now is an English-language website for Lviv, Ukraine’s «tech-friendly cultural hub.» It is produced by Tvoe Misto («Your City») media-hub, which also hosts regular problem-solving public forums to benefit the city and its people.